Paper on sublimation driven convection on Pluto published in Nature

If you have ever been cold when getting out of water on a warm sunny day, latent heat is to blame. The water on your skin evaporates, which requires energy (the aforementioned latent heat). Part of this energy is taken from your skin, effectively cooling it down and making you shiver in the process. The same phenomenon is at play when we use perspiration to regulate our body temperature. Latent heat is also involved when ice sublimates (that is to say, changes into gas), which occurs on Pluto.

The American space probe New Horizon made history when it performed the first (and to this date, only) fly-by of the dwarf planet Pluto on 14th July, 2015. The collected data was enough to change in drastic ways our understanding of this remote world. In particular, it showed that Pluto is still geologically active despite being far away from the Sun and having limited internal energy sources.

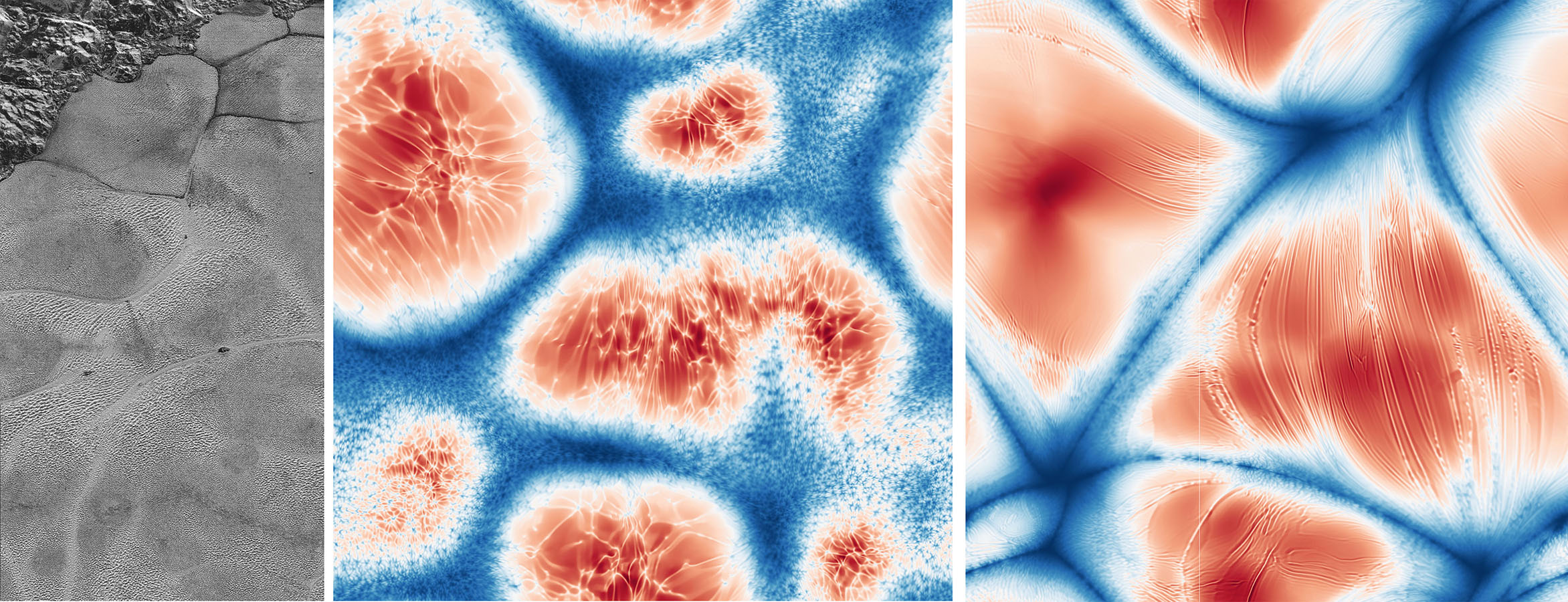

Perhaps the most striking feature on Pluto’s surface is Sputnik Planitia. This bright plain, slightly larger than France, is an impact crater filled with nitrogen ice. Pressure and temperature conditions at the surface of Pluto allow the gaseous nitrogen in its atmosphere to coexist with solid nitrogen. Climate models of Pluto predict exchange of nitrogen between the atmosphere of Pluto and Sputnik Planitia. Moreover, the surface of the ice exhibits remarkable polygonal features (see Figure). This is a manifestation of thermal convection in the nitrogen ice, constantly organizing and renewing the surface of the ice. The buoyancy source for such convection remained enigmatic, as the heat coming from Pluto’s interior would produce a surface topography in discrepancy with the observations.

In a study published on December 16th in Nature, Adrien Morison, Gaël Choblet and myself show that sublimation of the nitrogen ice powers convection in the ice layer of Sputnik Planitia by cooling down its surface. Manifestions of that sublimation are visible at the surface of the ice, in particular the uneven structure at small scale visible on the picture. Studying the growth of those structure from the centers of the polygons to their boundaries even allowed quantification of the convection in the ice layer: surface velocities of the ice are estimated to be similar to that of tectonic plates on Earth. In the study at hand, numerical simulations show that the cooling from sublimation is able to power convection in a way that is consistent with numerous data coming from New Horizons and following studies: size of polygons, amplitude of topography and surface velocities. It is also consistent with the timescale at which climate models predict sublimation of Sputnik Planitia, around 1 or 2 million years.

The dynamics of this nitrogen ice layer is in a way more similar to the dynamics of Earth’s oceans rather than that of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s icy moons: it is powered by the climate. Such climate-powered dynamics of a solid layer could also occur at the surface of other planetary bodies, such as Triton (one of Neptune’s moons), or Eris and Makemake (from Kuiper’s Belt).

Check out the paper on the journal’s webpage.